Recently, students in Concordia’s Social Entrepreneurship class participated in a lively discussion about cleaning products. During their conversation, students would periodically scribble ideas on Post-it notes and place them on the whiteboard at the front of the classroom. Before long the board was covered with bright yellow and pink post-its. To the casual observer, teenagers discussing home care products might seem unusual, but for this particular group, the discussion was a necessary part of their design thinking process, a tool they use to solve complicated problems.

High School Entrepreneurs Rise to the Business Challenge

A capstone project for this high school course requires students to address a real-life challenge faced by a real business. In early spring they met with the founder of Soapnut Republic to do just that. Soapnut provides a home care product line that delivers non-toxic, allergen free and biodegradable products for cleaning and personal care. Founder, Kim Gililand, enlisted help from the students to tackle the following challenge: Create a plan to best leverage Soapnut’s online presence in China in order to gain followers and convert those followers to buyers. While this may seem a complicated issue to tackle—especially if one is unfamiliar with cleaning products and the Chinese market—through design thinking, the students were able to meet this challenge head on.

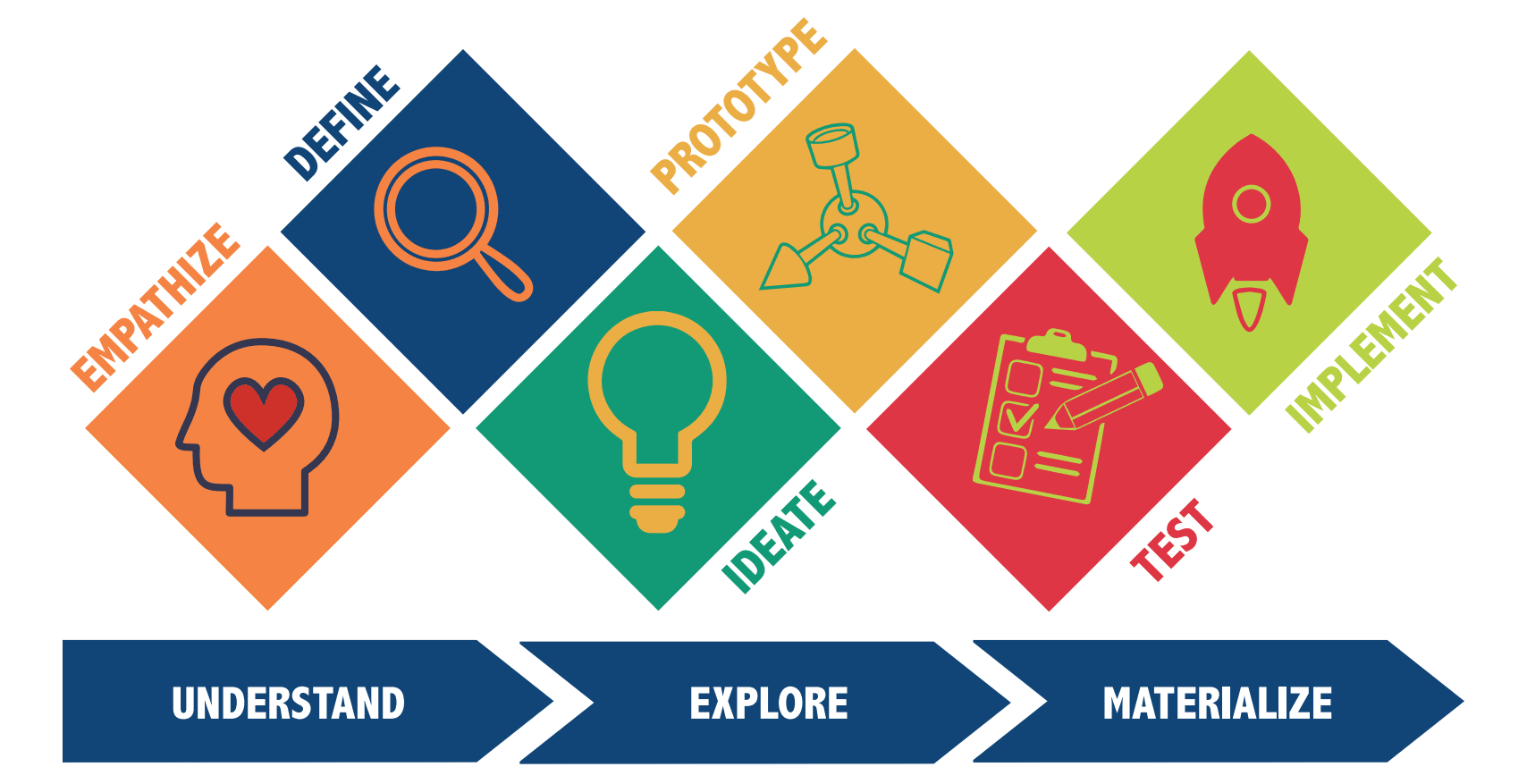

Design thinking is a way to solve authentic challenges utilizing a human-centered approach. It serves as a framework to redefine problems as opportunities and work toward viable solutions.

The first step in the design thinking process is to empathize. Conducting empathy interviews allows one to better understand the needs of the people they are designing for. In the case of our Social Entrepreneurship students, empathy interviews led to conversations with members of the school faculty and staff about their cleaning product preferences. The students also sat down with their parents and aiyis to learn what motivates their decisions when choosing home care products.

Back in the classroom, students decided on a pertinent “point of view” statement as part of the defining stage of their design work. Focusing their point of view allowed students to paint a picture of the opportunities unearthed during the interview process. For one group, the point of view statement they developed read: “The customer needs a way to make cleaning convenient and safe because of the lack of time and fakes online.”

Students then began the process of ideation, brainstorming “How Might We” questions centered around their point of view. (This is where the Post-its came in.) “How might we emphasize the convenience and safety of cleaning products?” posted one student. “How might we improve the shopping experience for the customer?” wrote another. In generating possible solutions for their user, students were encouraged to go for quantity and suspend judgement—no ideas were off limits.

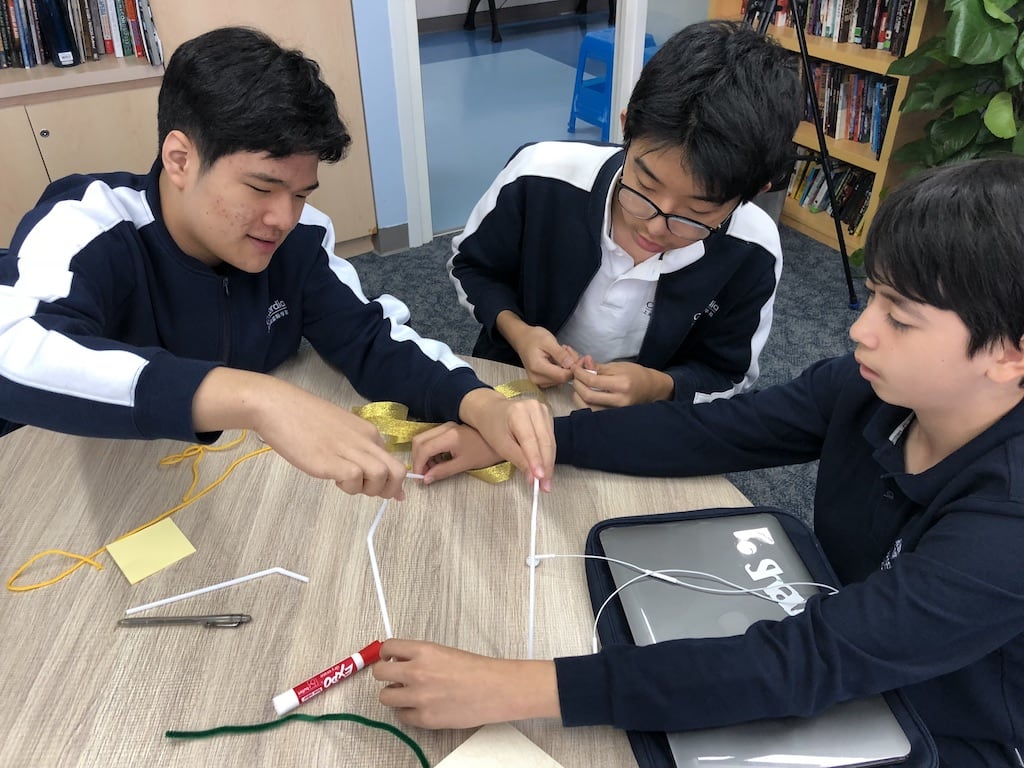

Having amassed several ideas, students then chose one idea for which to create a low-fidelity prototype that could be tested by actual users. While not all ideas generated lead to viable solutions, the process of ideating and prototyping was essential to the process. Each misstep and flaw led to iteration and improvement, encouraging students to embrace the notion of “failing forward.” With data from their user tests, students presented their final prototypes along with validation to Soapnut, for approval and implementation.

“Using design thinking as a road map, this complicated challenge became less overwhelming,” says Social Entrepreneurship teacher Anne Love. “Talking to the students, it is clear that they learned how to spend time with the problem and deeply understand it as opposed to jumping right to a solution, which may seem like the easiest thing to do.”

Middle Schoolers "Design Think" Their Lunchroom Experience

Back in June 2018 and again in February 2019, trainers from Stanford University’s d.school came to Concordia to lead members of the faculty and staff through a series of design thinking workshops. Since then, design thinkers have emerged from every corner of the campus, taking on a range of challenges that touch virtually all aspects of school life.

In the middle school, students used the design thinking model to address, “How might we improve the lunch experience in the school cafe?” Conducting empathy interviews with fellow students and carrying out field research at neighboring restaurants, the students took on topics from seating arrangements for inclusivity and better conversation to new ways to educate diners about making healthier food choices.

In the middle school, students used the design thinking model to address, “How might we improve the lunch experience in the school cafe?” Conducting empathy interviews with fellow students and carrying out field research at neighboring restaurants, the students took on topics from seating arrangements for inclusivity and better conversation to new ways to educate diners about making healthier food choices.

After completing each step in the process, students presented their prototypes and findings to their teachers and classmates. The next step for the students will be to present their work to school administration with the goal of fully implementing many of their ideas in order to improve and enhance the school dining experience.

To eighth grade teachers Michael Lambert and Holly Raatz, the bias toward action that is rooted in design thinking echoes the school’s philosophy of learning by doing, making the process more about “creating innovators rather than any particular innovation.”

Elementary Students Get Younger Learners Engaged in Math

In elementary school, grade three students interviewed students in grade two in order to find creative ways to make their geometry math units more engaging. With help from their teachers, students ideated around the question, “How might we make learning about shapes more engaging?” The third graders discovered that their grade two counterparts needed more interactive games that would help make the challenging vocabulary of their geometry unit stick. What ensued was a design thinking project that allowed students to design for the needs of other students, while deepening their own understanding of mathematical language and content.

In elementary school, grade three students interviewed students in grade two in order to find creative ways to make their geometry math units more engaging. With help from their teachers, students ideated around the question, “How might we make learning about shapes more engaging?” The third graders discovered that their grade two counterparts needed more interactive games that would help make the challenging vocabulary of their geometry unit stick. What ensued was a design thinking project that allowed students to design for the needs of other students, while deepening their own understanding of mathematical language and content.

“As educators, we know the deepest form of understanding comes when we are able to teach the concepts we’ve learned or are learning,” says Elementary School STEM coach Kristy Godbout. “It is very rare that students have authentic opportunities to do just that—become the teachers and facilitators of the concepts they are learning.”

The impact of design thinking on student learning has exceeded the expectations of the educators at Concordia. Not only have those involved become more creative and innovative risk-takers, they have become models for these qualities, and their students are following their example. The act of kids designing for others creates relationships across grade levels, and it is something educators hope to continue at Concordia, says Godbout. “It is an act of service, an application of learning, and it deepens all of the student learning outcomes, truly offering the holistic experience we strive to provide.”